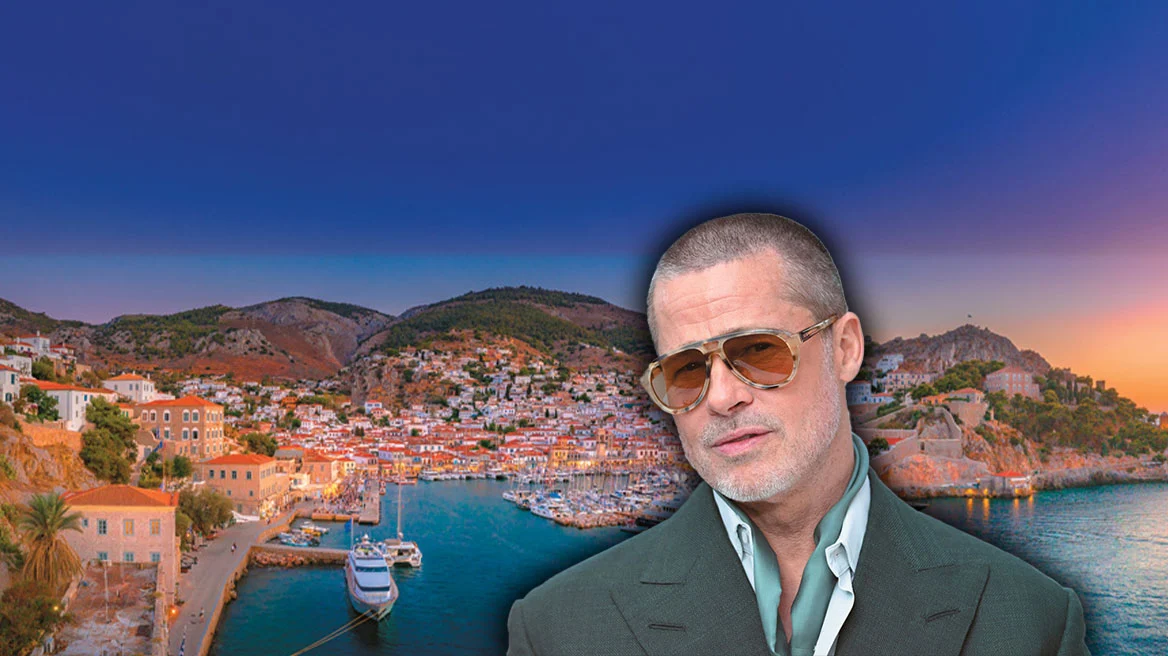

Piraeus–Hydra

Piraeus to Hydra. A short sea journey and you change centuries, images, and habits. You gaze at the amphitheatrically built settlement—an architectural jewel with a remarkable historical heritage. You forget the sound of cars. You keep walking and walking, eager to explore the harbor and its waterfront, the neighborhoods, narrow alleys, small squares, and then Kiafa.

You greet people good morning and good evening. You peek through the few open windows into the interiors of mansions and captains’ houses built in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, during Hydra’s economic prosperity thanks to its fleet. That was when the well-traveled Hydriots brought back knowledge, experience, wealth, and precious objects from Mediterranean ports.

Thirty mansions and three hundred captains’ houses from that era adorn the town. Built with gray stone from Hydra and Dokos, wood and tile roofs, colorful doors and white-trimmed windows, they bask in the spring sun. While austere on the outside, their high-ceilinged salons and bedrooms were richly decorated—as you’ll see inside hotels housed in former mansions and in the museums of Lazaros and Pavlos Kountouriotis. Ceiling frescoes, marble floors with geometric designs, expensive carpets, fine furniture, antiques, decorative objects, and ornate dinner services—all brought from Mediterranean ports—transformed interiors into Renaissance-style Genoese palaces. You can almost imagine the evening gatherings in music and dance halls attended by Hydra’s “high society.”

A Stroll Around the Harbor and Its Landmarks

A uniquely harmonious settlement of multi-level houses—three or even four stories high—with hidden gardens faces the sea, whispering stories of glory, seamanship, wars, destruction, and triumphs.

Stories of Sophia Loren, who made Hydra famous in the 1950s with the film Boy on a Dolphin. Stories of the celebrities who passed through in the 1960s and ’70s, creating their own VIP enclave—“the Saint-Tropez of the Saronic Gulf.” Legends such as John Lennon, Eric Clapton, The Rolling Stones, Aristotle Onassis and Maria Callas, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Melina Mercouri, and Jules Dassin. And of course, Hydra’s beloved Leonard Cohen, who owned a house on the island—still marked on Google Maps.

Hydra is also the birthplace of poet Miltos Sachtouris and attracted intellectuals and artists such as Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, George Seferis, Nikos Engonopoulos, Henry Miller, and Panagiotis Tetsis.

Today, cosmopolitan life continues in a milder form. Exhibition openings, summer festivals, conferences, weddings, and events fill the harbor with yachts and the cobbled streets with familiar faces from the worlds of business and celebrity. Many Greek and foreign entrepreneurs have invested in Hydra, restoring old mansions as summer homes.

Yet on this November morning, the echoes of summer have faded. Daily life unfolds quietly. Locals sip coffee along the waterfront, discussing the past season and exchanging news. Some shops and restaurants prepare to close for winter, others set up for lunch and dinner.

Museums and Monuments

At the eastern edge of the harbor stands the statue of Admiral Andreas Miaoulis, erected in 1993. His bones were transferred to Hydra in 1985 and are buried at its base. Nearby stand twin Venetian buildings that once served as a hospital and gunpowder store; today one houses the Melina Mercouri municipal art and concert hall, the other the port authority.

Close by is the impressive Historical Archive–Museum of Hydra, founded in 1918—among the first in Greece, alongside the General State Archives. It contains 19th-century paintings, relics of the 1821 War of Independence, traditional Hydra costumes, maps, navigation instruments, elaborate ship figureheads, and 18,000 historical documents.

In the center of the harbor stands the Monastery and Cathedral of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, Hydra’s metropolitan church, founded in the 17th century. Its marble iconostasis and candlelit chandeliers are striking—especially the golden six-branched chandelier near the Royal Gate, brought from France or Spain and adorned with the heads of the French Louis kings.

On the western side lies the mansion of Pavlos Kountouriotis, built before 1821 by Georgios Kountouriotis and later renovated by his grandson, Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis—future minister of the Navy and President of the Hellenic Republic. Today it operates as a museum.

Further along is the western bastion known as the Periptero, where visitors pause beside massive cannons to admire the sea view. In summer, the docks of Spilia and Hydronetta fill with swimmers and diners at waterfront restaurants; today they are nearly empty.

Kaminia and the Ascent to Kiafa

Walking past the small Avlaki beach, I continue toward Kaminia, a picturesque cluster of houses, many now villas or boutique accommodations. Its emblem is the “Red House,” the old Miaoulis residence built in 1786, where scenes from Boy on a Dolphin and other films were shot.

Later, I visit the Lazaros Kountouriotis Museum, housed in a magnificent late 18th-century mansion and operating as a branch of the National Historical Museum. It displays family heirlooms, furniture, paintings, and folk art collections.

Climbing to Kiafa—the island’s original settlement dating back to the 15th century—I wander through narrow, maze-like alleys lined with small shops and workshops. Churches such as Saint John the Faster, with 17th-century frescoes, Saint Paraskevi with its panoramic harbor view, and Saint Constantine the Hydriot crown the hill.

Descending again to catch the last high-speed ferry, I admire Hydra—declared a protected historic site and landscape of outstanding natural beauty. Here, uncontrolled construction is forbidden. Each visit feels like entering a time capsule, preserving the works of its people and the aura of its remarkable history—making you forget, completely, the noise of city life.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions